Bike weight has always been important, but how much do you really know about nutrition? Photo courtesy of PuuikiBeach via Flickr

By now, you’ve probably read about our newest noob columnist, Josh. He’s taken a hard look at how the first season of racing went overall, looked at his first race attempts, and now he’s tackling the technical side of things by exploring nutrition.

by Josh Schwiesow

Most cyclists spend some time focusing on their weight, and I am certainly no exception. It is obviously easier to race for 45 minutes or so if you aren’t overweight. And so, at some point, it occurred to me that I’d never taken a nutrition course. If possible, I was a bigger noob at eating well than I was at cyclocross last year.

As I mentioned previously, I’m a recent cancer survivor. While most cancer patients lose weight, I gained about 30 pounds due to a loss of willpower, a big decrease in exercise, and constantly trying to “cover” the chemotherapy taste and nausea. By my first cyclocross season, while I’d lost most of the cancer weight, I had no idea where I should be. According to the NHLBI, my 6’5” and 190-195 pounds was within the “normal weight range.” But I wondered if there were more gains to be made, as I’d previously felt faster climbing when I weighed around 185 pounds.

Cyclocross culture, even in the United States, includes a lot of Belgian beer, frites (a.k.a. French fries), and bacon. I embraced the Belgian beer and frites, anyway, if not the bacon. Indulging in these items in any sort of excess doesn’t exactly lead to weight loss, but admittedly the same could be said about indulging in most foods in excess. As the season wound down, I took the opportunity to re-evaluate my diet, and so began my noob education on nutrition, starting from a very low baseline.

My guess was that I ate far too many carbohydrates, too many calories, and not nearly enough protein. I had no actual data to know, so it was just a guess based on the fact that I far preferred starchy meals to meat. In years past, I had counted calories and macronutrient percentages using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, but I thought I’d do something a little differently this time, and so I signed up for the free version of Training Peaks.

The Training Peaks software has been quite popular among cyclists for years, but it was all new to me. My honest early impression was that it was not intuitive and it took a few weeks to really make things work quickly, but after a few months, I loved the program. It took me even longer to figure out their mobile applications, but once I did, nutrition estimation became possible even when traveling.

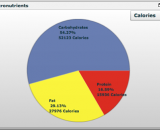

It didn’t take long for the program to illustrate I wasn’t quite “60/20/20.” One somewhat controversial rule of thumb for nutrition suggests your macronutrients should be 60% carbohydrate, 20% fat, and 20% protein. I was lower than that on protein, but higher on fat. Given my affinity for candy and chocolate, this should not have been a surprise.

My initial goal was less to track workouts and more just to create a food log. I first estimated my basal / resting metabolic rate using both equations I found on the internet, as well as the tools within Training Peaks. Not accounting for an active lifestyle using the “1.5 – 1.7x fudge factor,” I found my daily intake should probably be in the 2,000 calories / day rate before any exercise or adjustments for lifestyle, which is similar to the long-standing “Recommended Daily Allowance” for Americans. I made estimates of my additional caloric needs for exercise using a Garmin training device and the Garmin Connect website.

I was determined to not go on a “diet” per se, but rather to balance calories, and make small changes towards improving my diet. One of the biggest factors when counting calories is knowing that if you must count them, it is often easier to not eat the calories in the first place – at least when you first begin. This definitely worked for me as my caloric intake immediately decreased within the first few weeks.

I was excited to see Molly Hurford’s interview with Matt Fitzgerald to speak about his book “Racing Weight: How to get lean for peak performance.” Looking at this interview, the author refers to a formula for finding your appropriate weight, without actually giving away the formula. As it turns out, it is a bit more work than can be easily shared in an interview or noob blog, but I was intrigued enough to order and read the book. Although there are two methods for calculating your “race weight,” the faster of the two put mine right around 177.

It didn’t take me long to get to around 178 or 180 pounds using this method, however, over those several weeks I felt as though I had lost some “snap” on the bike. I didn’t have the same acceleration I had during my weekly sessions on the track, and I was all but lost in any sort of bunch sprint. I later learned this is a really common mistake for noobs to make, and I had probably lost more muscle than anything despite consistent exercise. My training plan called for a volume of 10 to 15 hours per week, and I was reaching these goals despite the caloric deficit.

This presented a curious problem, and one in which I have not yet solved. If you foolishly lose weight too quickly and lose muscle and speed, how do you regain it? I had set personal bests on a mountain climb time-trial and local run. However, my “flying one lap” on the velodrome increased noticeably, along with several other similar distances. For cyclocross, this would translate to an inability to create multiple accelerations, one after another, which is obviously not a good way to race.

I don’t feel as though this weight loss was unhealthy as I was still consuming an average of more than 3000 calories daily. Additionally, I was observing what my carbohydrate/fat/protein ratios were doing at that time. At least I had the insight not to try something like this during the season.

As promised for this blog, I had hoped to bring in an expert when it may further illuminate lessons for the cyclocross noob. When we next visit nutrition, I’ll share the lessons I’ve learned!

Here’s the Noob Hand-Up:

- Belgian Beers and Frites should not be passed up in the name of weight loss. All things in moderation, but be sure to enjoy these well-deserved treats.

- Lighter is usually faster, but too light too soon likely means loss of muscle.

- The use of electronic tools and calculators can really help to get a handle on calorie counting and calorie burning.

- Using a guideline macronutrient ratio as a hard and fast rule could be as faulty as not adhering to any sort of plan. There is a lot of controversy regarding optimal ratios, do your own homework and consider consulting an expert, such as a nutritionist, dietician, or coach!

- Speaking of which, as always, don’t take our word for it, and talk to a nutritionist or your doctor before starting any kind of diet plan.