The growth of cyclocross and gravel has seen a corresponding abundance of discipline-specific products. From tubeless tires and wheels, to drivetrains, to clothing, there’s no shortage of ’cross and gravel gear.

But, even with today’s highly-specialized and often proprietary components and processes, there’s still room for DIY solutions to questions that at first blush seemingly only a handful of riders have. But stop and think about the sport’s growth, and that not every rider is going to be on the latest gear, and instead maybe piecing together a bike from spare parts. In this case, homegrown solutions can make more sense or be more fun. And let’s face it; we’re interested in riders’ modifications and customizations as they spawn new ideas and possibilities for everyone.

Paul Townsend in the UK recently sent us his modification to a Shimano Ultegra Di2 rear derailleur, having set it up with a clutch mechanism to make it more reliable for single chainring (1X) use. It’s a detailed Mechanical Monday piece that highlights advanced bike hacking in our sport.

Why do this?

A close look at Katerina Nash and Sven Nys’ Shimano Di2-equipped single chainring cyclocross bikes would suggest that cyclocrossers even at the top end of our sport are faced with the challenge of building a reliable single chainring Di2 setup.

To hear Townsend’s explanation, despite the fact that one could now run an XTR Di2 rear derailleur as a solution for those with electric drivetrains, it’s a good single chainring modification for those who are still running 10-speed and don’t want or need a wide-range cassette. It’s also good for those running Di2 setups who don’t want to purchase a new derailleur. Not to mention the satisfaction of having a unique, homemade rear derailleur.

Given Townsend’s background—he has 20 years experience as a design engineer working on plastic moldings as well as pressed and machined parts for compressed air breathing mechanisms—this may not be a project for the average home mechanic. But it does show the possibilities. Townsend has, in fact, also built his own hubs and his own cantilever brakes. So fabricating his own key components is nothing new for him.

As for the modified derailleur, Townsend says he “started playing around with Di2 derailleurs in 2014 on my mountain bike with a custom cage, similar to the K-Edge and SRAM X-Horizon type, to run a modified Ultegra Di2 1×10 set-up with an 11-42 cassette. And I always thought there must be a way to do a clutch mechanism with a Di2 set-up.”

Townsend figures there were about three versions before the final seen in the photos and that he spent about six months working up the final iteration. “I have 3-year-old twin boys, so not a lot of time for riding or bikes.” That said, he’s done versions for both 10 and 11-speed Ultegra Di2 rear derailleurs.

So how did he do it? “My first attempts where to use the SRAM Type 2 clutch with the SRAM knuckle machined down and bonded into a carrier piece to attach it to the Ultegra Di2 arms. It worked out okay, but adjusting the clutch tension wasn’t easy,” says Townsend.

Townsend really started on the project March 2015. “I was building a new cyclocross bike and wanted a Di2/clutch mechanism on that bike.” After interest from a fellow online forum member Townsend looked into other options aside from his prior efforts bonding the SRAM knuckle and decided that modeling a new part on 3D CAD and having it made would be a better solution.

“The first real challenge was working out all the angles of the pivots, and the relative positions to mount everything. The simplest way was to bite the bullet and destroy an Ultegra Di2 knuckle and a Deore clutch knuckle and simply cut and epoxy the parts together. This let me play around with the relative positions of everything and trial a rough prototype in the bike stand.”

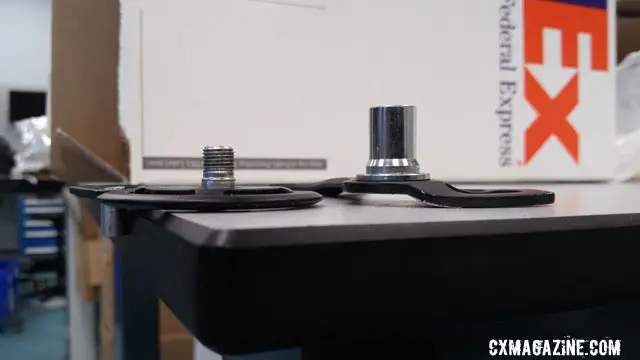

An exploded view of Paul Townsend’s modified Ultegra Di2 derailleur with 3D CAD designed knuckle and RADR cage providing a clutch mechanism for the electronic component.

Once he had a viable model, Townsend measured all the angles and positions and started 3D CAD modeling. What he used was a “parametric modeling system so if the pitch of a hole was wrong it could be moved and all the associated features would move with it and the model could be regenerated with the new parameters and form,” notes Townsend. Once a reasonably likely final shape was settled on, rapid prototype parts were made. “A couple of iterations of this were required because of the top cap design and wanting to move the clutch activation lever.”

“The next challenge,” according to Townsend, “was getting the best balance between the cage spring force, the clutch force, and the B knuckle spring force.” As it turned out, Townsend compromised on the relationship between these. “The cage has the same return spring force as the road cage, which is about half that of the standard MTB cage, but the additional load of the clutch meant that most of the movement for chain tensioning across the cassette was being done by the B knuckle spring, and that in the smaller cassette cogs the derailleur was too far away from the cassette leading to poor shifting.” Townsend’s solution was to increase the B tension spring to move the derailleur closer to the cassette.

“Because I wanted to run an 11-34 cassette, a longer B tension screw was needed along with a suitable cage. The (OneUp) Radr cage worked better due to its increased take up over the (Shimano) Zee cage and the offset top pulley remaining closer to the cassette across the gear range.”

Paul Townsend’s modified Ultegra Di2 derailleur with 3D CAD designed knuckle and RADR cage providing a clutch mechanism for the electronic component.

Once Townsend had the final design it was time for manufacturing. “Parts where run off by a rapid prototype bureau as an SLS laser sintered part.” For the uninitiated, “[t]his basically uses a laser to melt tiny granules of nylon together to form the part.” Townsend pointed out that the EOS Nylon 12 material used carries an extremely high load capability. As for the cage pivot, “it runs in a hard anodized aluminum bearing sleeve within the knuckle, and new bushes were machined and pressed into the knuckle pivots.”

Townsend’s efforts weren’t without issues. “The only glitch I had,” he said “was on the initial install. All my measurements where based on using a road cage. I didn’t realize that the MTB derailleur has about 2mm less standoff between the end of the P knuckle and the pulleys’ center line. So a 2mm spacer and broader cage spring seal was machined to close the gap up.” After that, it was ready to go.

Townsend has also supplied other riders with the parts and instructions needed to perform their own conversions. Mike Wood has a modified Ultegra 6770 mechanism that now has a clutch and Zee cage. He’s run a Wolf Tooth narrow-wide and a Garbunk Melon ring, with the Ultegra 11-28 and XT 11-36 cassettes with no issues thus far.

“I’ve put two races on mine so far,” says Wood. He’s done the “San Francisco Superpro Race 1 and 3 and a few practice sessions in Golden Gate Park. Both races had pretty rough in sections and the chain had much less slap—I barely heard a peep from it—and it never came off or felt like it was about to. Shifting is as good as the original derailleur and provides good chain wrap around the cogs. The race in Vallejo had three boggy wet mud passes followed by a sand ride-then-run section and even though right after that everything on the bike started making noises there where no issues with multiple cog downshifting for a big climb where several others had chain issues. Even after some bobbles the chain was always in place ready to pedal upon remounting.”

Wood plans to convert his 6870 derailleur and will likely use an XT mid-length cage and its clutch.

Necessity is the mother of invention. Is an Ultegra Di2 clutch derailleur necessary? If you’re Townsend, yes. If you’re running a Di2 system and want to go 1X to reduce or eliminate chain slap and dropped chains, yes. Will we see a combination of the technologies directly from Shimano? Time will tell. Until then, here’s to homegrown modifications like Townsend’s.