Cyclocross fans have heard the tales. Massive crowds, the smell of frites, thumping beer tents, epic mud, partisan fans, ultra-tough courses and world-class racers.

Attending a top-level Belgian cyclocross race might be a chance to validate or dispel all the clichés, and such stories might very well be what draws you to take in a race in the motherland.

Yet knowing a pilgrimage to a big race like the Superprestige in Gavere (pronounced: ˈɣaːvərə) might be wasted if it’s spent purely in search of confirming preconceived notions, I seized an opportunity to attend the race in Gavere with eyes and lens wide open. I strolled, slid, and often sprinted around the venue, wondering what impressions, memories and images I’d capture.

In the end, the event over-delivered with memories, many unexpected. Come along for the trip through the photo essay below.

Small Town, Oversized Presence

At last count, Belgian's Gavere, in East Flanders, houses just under 13,000 residents.

Any event that doubles a town's population for a day is bound to dominate the local's attention, and for them, it (and the day after) are effectively local holidays.

Yet the Superprestige Gavere stop, held all but three years since 1983, is one of the oldest races and holds a special place in the sport's lore.

Part of Gavere's oversized presence is simply because of the venue and conditions. The wooded, hilly course on a military base often presents stunning fall foliage, tough climbs and descents, and yes, epic Belgian mud. For some riders, those characteristics give this race a larger footprint on the race calendar.

The Gavere course, held on a military base, is one of Europe's oldest and most scenic races, and shares some characteristics with Cincy's Devou venue. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

"Oh my gosh, it’s definitely one of my favorite courses," American Elle Anderson gushed. "It always stuck out in my mind as something for me. It’s so muddy, so gnarly. I just really like this course. This is a real highlight on the calendar."

Elle Anderson said she had an off day, but gushed about the Gavere course and its significance on the European cyclocross calendar. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Women. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Anderson puts Gavere up with the sand dune-filled Koksijde and the under-the-lights Diegem on the short list of top races for an American to attend.

For others, the race's history puts extra pressure on them to perform. U23 World Champ Eli Iserbyt, racing with the Elites at Gavere, said before taking the start that he tries to approach the race like any other, but he can't help but feel the pressure from those around him.

Asked whether Gavere's long history increases the importance of getting a good result, Iserbyt explained, “Yes, especially for the people around the team, for the sponsors, it’s more special than the other races.” [See our profile of Eli Iserbyt's World Championship-themed Ridley X-Night SL here.]

Pressure cooker in Gavere: Eli Iserbyt had a good start to sit in the top 10 before fading to 24th. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

It Takes a Village

Production of such a high-profile event demands more than a handful of volunteers. A day before the race, there must have been more than fifty people working feverishly to complete the build-out of the nearly-finished course. Construction demands dwarf any American event, simply because of the number and scale of the facilities required for the one-day event.

Fans take in lunch and beers in the VIP tent before the racing starts. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Three beer tents, food trucks, souvenir stands, a massive podium, television camera stands and wiring, multiple big screens, a flyover and finishing straight structures and electronics all required a massive team to set up.

Four men and a forklift were dedicated just to distribute the beer kegs throughout the course.

Ticket sales, at €12 a person, certainly help cover production costs, with an estimated 15,000 spectators attending the event.

While it takes a village to build up the course and facilities, the riders and their teams arrived Sunday and created their own village.

At a race that most racers drive to, it's breathtaking to see the number of campers the larger teams bring in. Marlux-Bingoal, one of the biggest teams in Belgium, brought Junior Men, Elite Women and Elite Men to the race. Its Elite racers alone took up an entire parking lot, with one camper for each rider. The Juniors had to find space in another lot. There was no room for them after the campers and mechanics for the Elites got set up.

Marlux Bingoal is one of the biggest teams in Europe, and just its Elite riders brought six campers. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

After seeing what European pros are used to, you might be more sympathetic to how different racing in America is for many of them. While many U.S. pros are used to living out of a suitcase, flying from UCI stop to UCI stop, the routine race day for many Euro racers involves a caravan of family members, support staff and creature comforts.

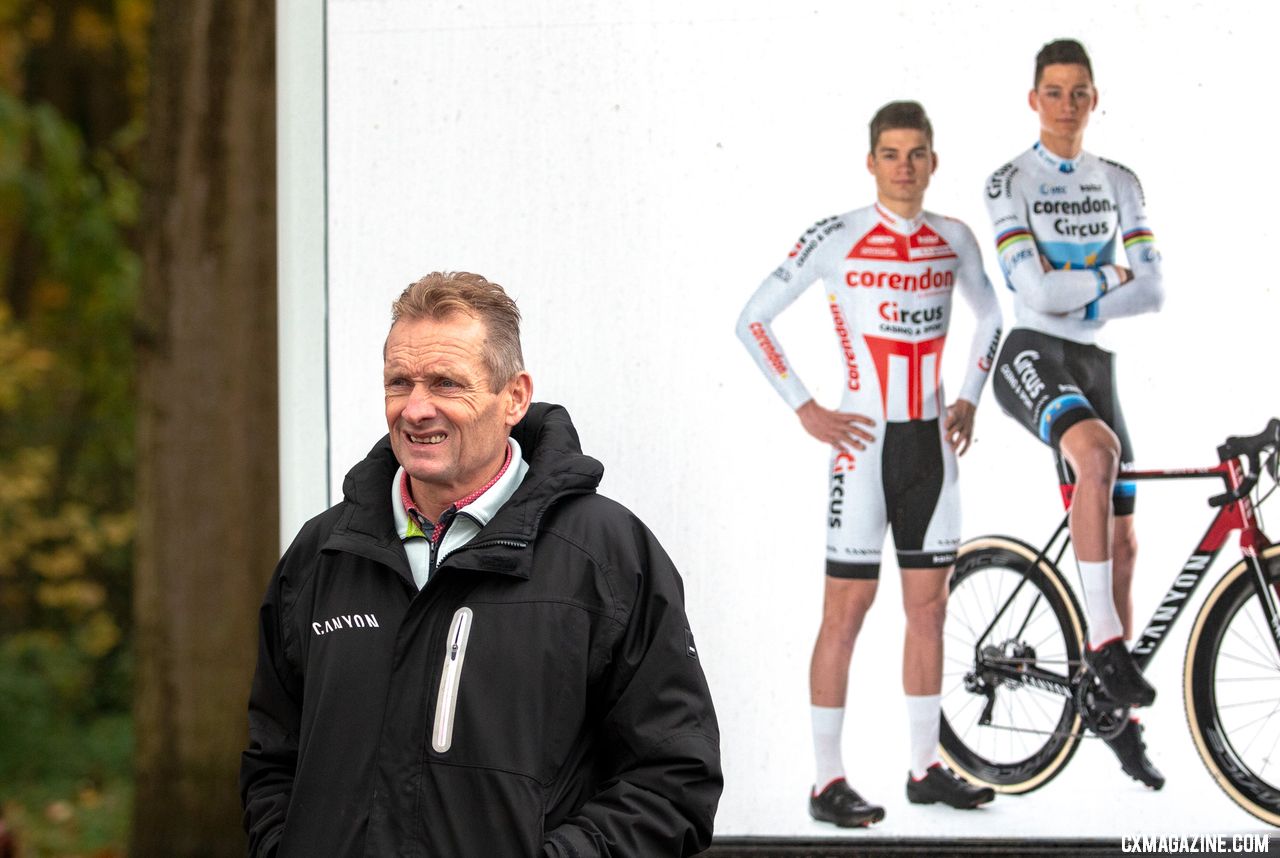

The biggest stars have the biggest presence. Mathieu van der Poel and his brother David shared the biggest camper on the lot, and it was just for their bikes and personal support staff.

The Van der Poel family, their bikes and their fans command the biggest presence at the Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

While the camper looked big enough to hold the whole cyclocross team, it's not their transportation vehicle. The brothers arrived late in a personal car before scurrying into the camper after a few autographs.

Next door, the team had its own souvenir tent, while there was also a fan club tent, a tent and camper for Sanne Cant.

The biggest souvenir stand was selling product from the biggest stars. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

If you're teammate Tom Meeusen or any other rider? You've got to find space somewhere else. There's no room for others, after you take into account all the fans.

Fans of all ages wait for a Mathieu van der Poel appearance, while his mechanic cleans up from the day's effort. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

It's a Family Affair

You might assume if you're a million Euro man, the reigning world champ or Koppenberg winner that you'd have plenty of support staff at your disposal, but even for the sport's top athletes, family members are a key component of a cyclocross pro's drivetrain.

Sanne Cant's father was busy prepping bikes and guarding chain ring secrets on race day.

European cyclocross is a family affair. Sanne Cant's dad prepares the race bikes, and guards her secret chainring combination. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Husbands, mothers, brothers were also put to work. While the very biggest stars might be able to afford a full team of paid staff members, it's the family members that make their path to stardom possible and affordable, and many remain in the role.

European cyclocross is a family affair. Koppenberg winner Kim van de Steene's dad pulls out spare wheels to show off their collection of matching but discontinued orange FMB tubulars. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

When asked if he gets paid by his son to do bike washing and adjustments, Eli Iserbyt's father just laughed.

European cyclocross is a family affair. Eli Iserbyt's mom cooks a pre-race meal while brother Oliver helps out. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Husbands are often leaders of the fan club and pit crew. Like Mark Legg, Stefan Wyman helps his national champion wife keep her bike and sport moving forward as she climbs to top-five finishes.

It's not just dads. Helen Wyman's husband Stef heads to the pit. European cyclocross is a family affair. 2018 Superprestige Gavere. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Former cyclocross world champion fathers don't even get a pass from race day duties, although they might be allowed a few minutes break.

A Course for Mortals, Favoring Immortals

Thanks to a rare opportunity to test out legs and equipment on the Gavere course on Saturday, I could better appreciate what the pros pulled off on Sunday.

While the entire course minus the one muddy run-up was rideable for my mediocre power and skills on Saturday, seeing the speeds that the Elite men and women blasted through a more chewed-up version of it a day later was awe-inspiring.

Sanne Cant, Fleur Nagengast and Annemarie Worst race to the first hairpin. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Women. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

While there were plenty of crashes on downhills and in turns, the mere fact that many of them bombed the descents with abandon, without riding their brakes, was impressive. The grade and speed of the descents is something that TV cameras don't quite render like standing inches from the racers does.

Eva Lechner flew Italy's colors to make it two Italians in the top six. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Women. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Even running speeds were at another level. Getting back on your bike as soon as possible isn't always the best option when your foot speed can outpace your muddy pedal mashing pace.

Up close, it's also easier to appreciate true greatness. Sure, some have lamented the unsuspenseful nature of Mathieu van der Poel's dominance, but up close, utter dominance and course prowess offer up their own beauty.

Watching the best in the world go wire-to-wire and make other superhumans look human is hard not to appreciate.

From the gun, Toon Aerts was the only one to keep Mathieu van der Poel within reach for a few laps. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Simple mastery of a course's toughest features doesn't get lost when you've already struggled to walk up or down them.

Even when a World Champ seems broken and crushed on screen after a typical Mathieu van der Poel attack, watching that same rider power up a tough, steep rise, aided by the sudden roar of the crowd, is energizing. In person, a losing ride turns into an impressive feat.

Wout van Aert had a tough day but rejoined Toon Aerts in the battle for second. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

The Slippery Slope of Confirmation Bias

While the course, family nature of cyclocross and sheer size of the infrastructure and rider areas all delivered surprises, it's still hard to avoid confirming the most-told stereotypes of Euro cyclocross.

Some of them are simply impossible not to notice. Early on in a race, the roar of the crowd amplified as soon riders approached, regardless of who was leading.

Yet when a Dutch star circled the course with a 30-second lead over two Belgians? One couldn't help but be startled when he passed by with little fanfare. It was eerily silent. If you didn't pay attention to his speed, you might have thought he was a lapped rider on parts of the course. Fans help photographers know the leader is coming in the States, but I learned that's not always the case in Belgium.

Mathieu van der Poel, with under two laps to go, enjoys a quiet ride with a single fan cheering on the course's bottom half. It was eerily quiet when the champ circled the course late in the race. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Fans were certainly spirited and rowdy, but in a partisan fashion. Most aren't participants on hand to watch top-level racing in general.

They're like any hardcore American professional sports fan, making the trip and buying a ticket to cheer on a local hero or favorite star.

Out on the course, the stereotype seems true, as most just cheer for just their favorites. But if you're someone different, you can capture the same attention as a star. Tetsuki Kaji from Japan made his Gavere debut to the amusement of fans, and got some of the loudest cheers as he tackled the muddy course.

Japan's Tetsuki Kaji may have received more cheers than Van der Poel in his 2018 Superprestige Gavere debut. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

The other oft-told tale from European cyclocross is of the beer tents. They're legendary in size, rowdiness and in staying power, and in Gavere, they more than lived up to their lore.

Three hours after the racing had finished, the tent was just starting to warm up, thanks in no small part to hundreds of fans now fully flushed from countless plastic cups of Jupiler or Cristal. The music was pumping, the beer was flowing, and locals predicted it would continue that way until midnight.

The beer tent was packed and hopping three hours after the race ended. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

It took ten minutes to make my way end-to-end through the tent. Perhaps because I was carrying two cameras, perhaps because as an Asian American I look a bit different than the other Belgians and European journalists I was with, I was swarmed and instantly separated from my group.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaAe6Rl8HLM

I was handed a beer, embraced into selfies and greeted with a number of non-threatening expressions that were mostly incomprehensible to this one-language American. Some asked if I was a journalist from China or Japan, but a shake of my head paired with a smile and a butchered form of "Amerikaanse" was my best attempt at an answer.

The beer tent was packed and hopping three hours after the race ended. 2018 Superprestige Gavere Men. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

As I stumbled out of the crowded tent, completely sober, fans less sober were getting re-acquainted with the foliage and mud of the legendary Gavere course and heading home with memories from the stellar day of racing.

I did the same. A few of them are below.