Advertisement

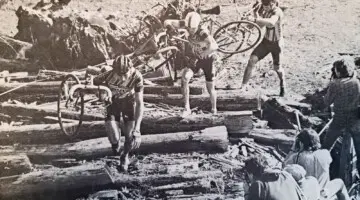

Cyclocross Magazine, along with a handful of other publications, had the opportunity to take a tour of Paul Component Engineering's factory, ride Chico's trails and tour the Sierra Nevada brewery in May last year. We're back at the 2017 event (with the only returning journalist), but in case you missed it, we're resurfacing the tale of our journey from last year. Come along for a photo-heavy factory and brewery tour, a look at the Paul Component Engineering's history and a slideshow filled with eye candy. And stay tuned to our Instagram feed for the latest from 2017.

Returning to the Roots

Fifteen years later, during our press event, it was rare to see Price not riding. He regularly commutes from his home to work, hits the local dirt on regular basis and still uses ride time to develop and refine new product ideas.

Paul Price’s current ride of choice, a custom Soulcraft Monster Cross machine, with 45c Fire Cross tires. © Cyclocross Magazine

His current ride of choice is once again a drop bar dirt bike, a custom Soulcraft with flared bars, Panaracer 45c Fire Cross clinchers, and of course, a slew of his own components. Our camp demo bikes weren’t much different: Surly Straggler disc brake bikes, with Bruce Gordon 43c Rock ’n Road clinchers, with a purple anodized stem, seatpost, brakes, quick releases, chain watcher, shifter mount and inline lever all made by Paul.

Our purple Paul-dressed Surly test bikes with Tall and Handsome post, Boxcar stems, Top Cap Light Mount, Klamper brakes, Chain Keeper, SRAM Shifter Mount, Cross Stop lever, Quick Releases and more. © Cyclocross Magazine

Rigid dirt riding is ingrained in Price’s DNA, even from his childhood years in the Bay Area before the mountain biking was “invented,” and he’s returned to his roots and reincorporated that style of riding into his weekly life. His company has followed. There’s no denying that despite the company targeting the mountain bike scene in the ’90s, now that most mountain bikes have full suspension, hydraulic brakes, dropper posts, and ever-evolving bottom bracket and axle standards, Paul’s components are really now more suited to the cyclocross, gravel, touring and vintage crowd, which seems just fine for Price. He doesn’t have a full suspension bike in his stable, and his own riding style and preferences are clearly reflected in his product lineup. It’s not about chasing cutting edge technology or even about gram savings, but prioritizing tried and true designs, precision and domestically sourced materials and parts.

For a small company with eleven employees, all under the roof of an old Texaco warehouse, the company has the ability to be nimble, identifying market needs and quickly prototyping products. But Price will be the first to admit the company is not exactly the fastest to bring its products to market. The Klamper mechanical disc brake took three years to develop and refine, and in that time, drop bar hydraulic disc brakes sliced into the market. “We always ride the crap out of them,” Price told me about the Klamper’s development, and the production version brake is at least the tenth iteration.

“We always ride the crap out of them” -Price

The company’s shop manager Jim had the programming and tooling all set for a production run of the brakes, but Price, after more riding, still wasn’t satisfied and had to go back to Jim for one final tweak. “I’d be like, this is really close, but we just have to change this one thing,” Price told Jim, requiring the tooling to be redone. “I’m sorry, but this thing has to be really good, this is a huge deal.”

I asked Price about his development process, and how big of a role computers play in product design, whether through finite element analysis (FEA) or 3D printing of prototypes. Price admits to looking into 3D printing, and has used a bit of FEA, but prefers to rely on his years of experience and ample ride time to validate and iterate designs. Products are created the old-fashioned way, most ideas coming from Price himself, with quick prototypes often machined manually in his side shop, which houses all the manual machines.

“We ride the crap out of everything,” Price says, and he’s certainly no slouch on the drop bar monster cross bike whether he’s product testing or just out for fun. © A. Yee / Cyclocross Magazine

Then the ideas are ridden, refined and then the cycle is repeated until Price is happy with the performance and reliability before handing off to his engineer to program the final products into the computer-controlled milling machines and lathes. In-house polishing, out-sourced anodizing and mirror polishing, followed by in-house assembly and packaging all draw out the time to market from an idea to final product typically to a year, minimum.

“I’m sorry, but this thing has to be really good, this is a huge deal.” -Price

With some rapidly evolving “standards” like brake mounts, bottom bracket, axle configurations and freehub offerings, occasionally Paul Component Engineering is late to the game. His Set and Forget thru axles, shown at last year’s Interbike, won’t be released until August. That sort of timing seems to suit Price (and his customers) just fine. He’s not after the bleeding edge customer, but the one who might sit on the sidelines to see how things shake out before adopting a new standard. It’s also safer, so that the company doesn’t invest a lot of time and resources developing a new product for a dying market, like 135mm or 130mm disc brake hubs.

Paul Component Engineering started with quick releases, and they’re new and improved and back in the line up, but still with an internal cam, thank goodness. The Set and Forget thru axles will be released this August. © Cyclocross Magazine

Even without rapid prototyping via 3D printing, Paul Component Engineering is able to refine products faster than large scale manufacturers because of the way it machines its products in batches. Materials and manufacturing geeks may discount products from companies like Paul Component Engineering because they are machined from aluminum billet as opposed to forged, which Price admits can, if used appropriately, result in stronger or lighter products in some applications.

Price explains that forging is first and foremost unfeasible for a small domestic manufacturer looking to make small batches of unique, proprietary components. Price says the investment, facilities and setup to create the dies of a profitable product typically requires the company to sell “a million units” and even after forging, the product still requires machining. Instead, Price focuses his attention on precision and durability, creating products to a .001 inch tolerance in order to minimize play and maximize quality. Moving pieces fit tightly together, operate smoothly with zero play, and as a result, tend to be supremely reliable even if it’s not attracting hardcore weight weenies.

His approach to cantilever and V-brakes showcase this approach. After getting frustrated by all the variability in cantilever brake post lengths, diameter and roundness and the resulting play, squeal and stickiness in brake performance, Price looked to eliminate these variables. He did it by designing brakes that pivot on their own internal bushing that mounts on the canti stud. Smooth operation, with no play. Brands like Speedvagen liked the system so much they designed cyclocross frames specifically around these brakes.